Description

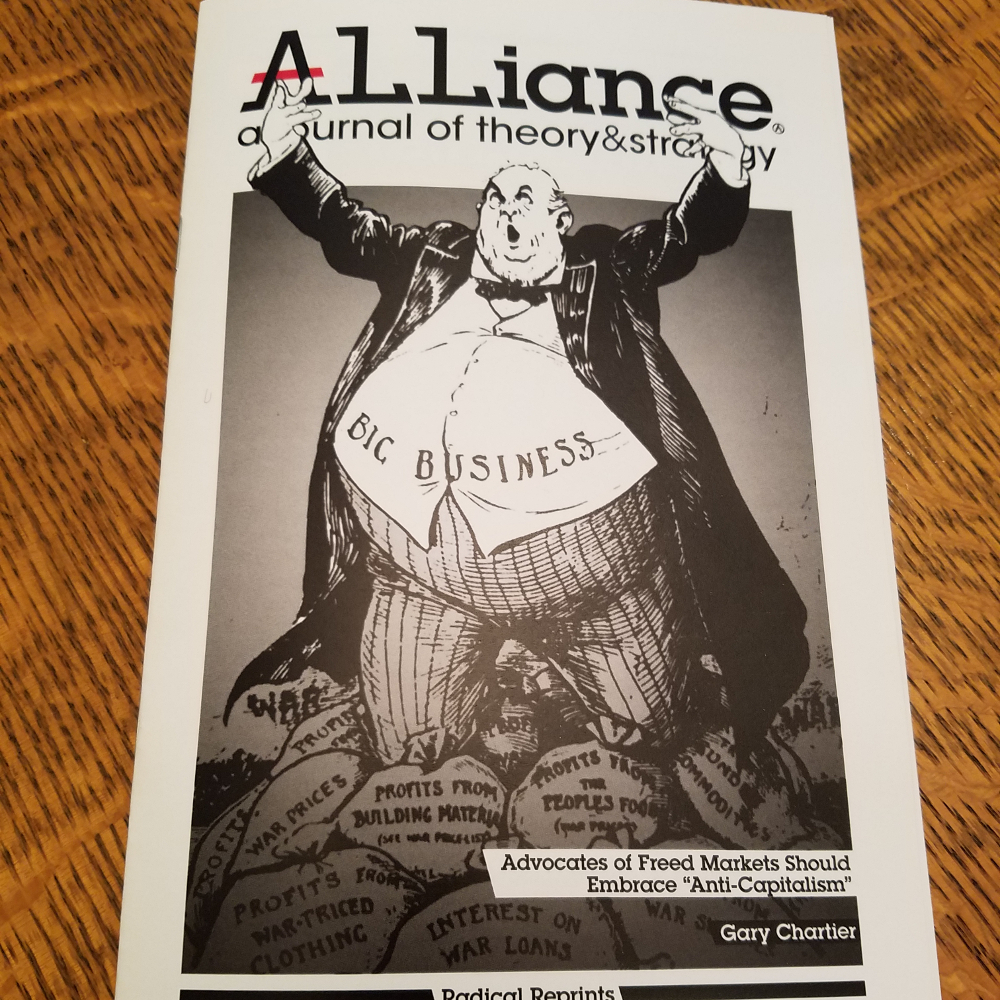

We libertarians defend economic freedom, not big business. We advocate free markets, not the corporate economy. And what would freed markets look like? Nothing like the controlled markets we have today. But how often do we hear mass unemployment, financial crisis, ecological catastrophe, and the economic status quo attributed to the voraciousness of “unfettered free markets”? As if they were all around us!

The crises laid at the feet of laissez faire are the crises of markets that are nothing if not fettered. When critics confront us with corporate malfeasance, structural poverty, or socioeconomic marginalization, we should be clear that market principles do not require defending big business at all costs, and that much of what our critics condemn results from government regulation and legal privileges. As a model for analyzing the political edge of corporate power and defending markets from the bottom up, we twenty-first-century libertarians might look to our nineteenth-century roots—to the insights of the American individualists, especially their most talented exponent, Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (1854–1939), editor of the free-market anarchist journal Liberty.

Conventional textbook treatments portray the American Gilded Age as one of relentless exploitation and economic laissez faire. But Tucker argued that the stereotypical features of capitalism in his day were products not of the market form, but of markets deformed by political privileges. Tucker did not use this terminology, but for the sake of analysis we might delineate four patterns of deformation that especially concerned him: captive markets, ratchet effects, concentration of ownership, and insulation of incumbents. …